Halin (Hanlin, Halin-gyi)

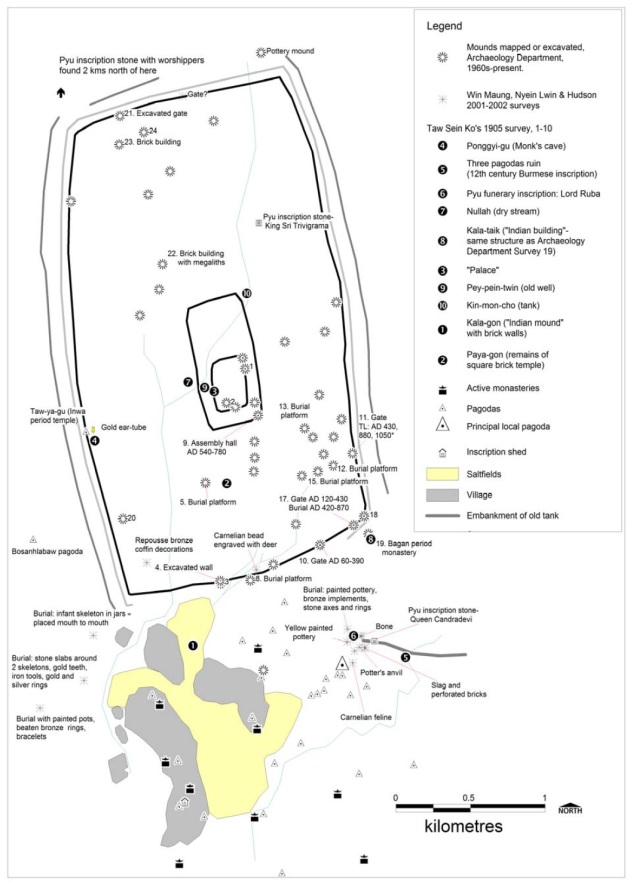

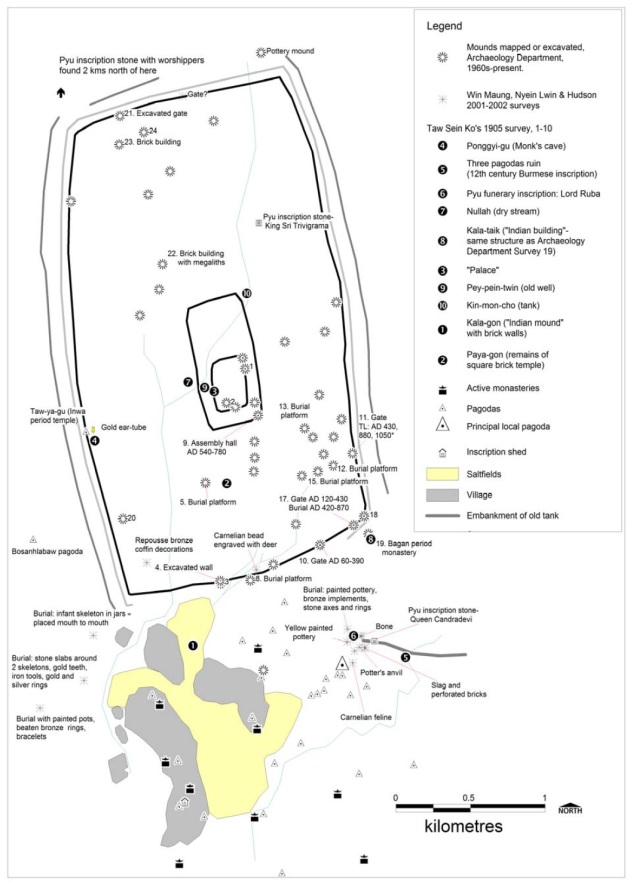

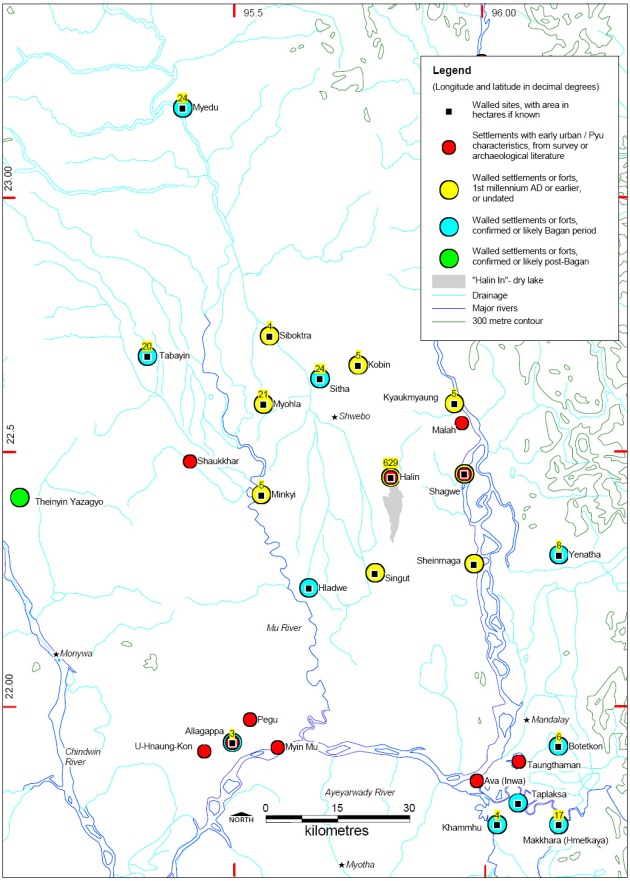

Halin (Chart 1, Figure 95 & Figure 99), with its substantial record of Late Prehistoric materials which appear to be linked to ongoing salt exploitation, is a special case in the expansion from the homeland. It is the only one of the four major sites with demonstrated and substantial pre-urban occupation of what later became a walled settlement, although it may be more accurate to say, since most of the known Late Prehistoric finds are south of the walls adjacent to the salt fields, that the walled complex was built beside, rather than on, the earlier area of occupation. Salt extraction has been recorded since the colonial period (Scott 1900: 116 Vol 1, Part 2 & 295-296 Vol 2, Part 1; Scott 1921: 253; Williamson 1929: 124-126, 141-143; Nyo Win 2001a) and remains of broad earthenware bowls that may have been precursors of the metal troughs currently used for reducing brine to salt have been recovered by local farmers, with some examples kept in the Nine Banyan Trees Monastery museum at Halin.

Iron Hoes, Adzes And Spearheads Halin (Halin Monastery Museum)

Coins Excavated At Halin

Characteristic Halin Srivatsa Rising Sun Coin

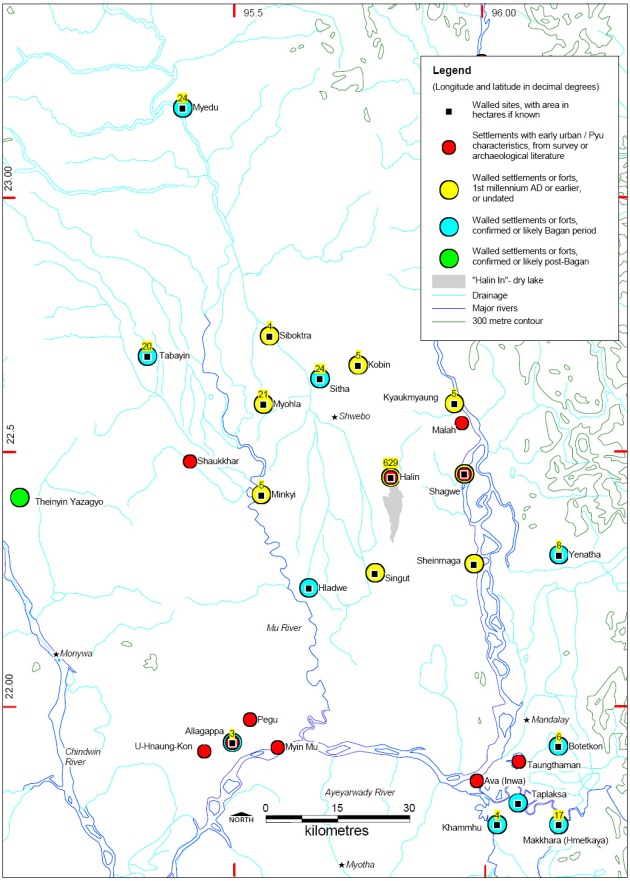

The geographical location of Halin supports the idea of a special function such as salt production rather than the prehistoric exploitation of networks of local streams for irrigation (see page 126). Maps (Figure 95) show the former bed of the Mu to the east of the present Mu river (Digital Chart of the World 1993), and a largely dry lake south of Halin (Burma One Inch series, 84 N/15). The geologically disrupted drainage system suggests that in prehistoric times this area may not have had the same access to irrigation resources as Beikthano or Maingmaw. In the Bagan period (Figure 96), the Mu canal was built from Myedu in the north, draining into the lake, Halin In, as the area was opened up for irrigated farming, and this system was extended in colonial times (Aung-Thwin 1990: 22-26, 72), but there is nothing to suggest that there was an earlier system of canal irrigation. The Halin/Shwebo area contains a number of Bagan period inscriptions (Figure 96), and there are similarities to Bagan in ceramics, with a red libation jar from Halin overpainted in white lines and dots (Myint Aung 2003: 112-113) comparable to a sample excavated in Bagan in 2003 (page 230).

Gold Filled Teeth Halin

Bronze Sword Handle Halin

Bronze Sword Handle Pommel Of Previous Figure Halin

Bronze Sword Handles Reverse View Of items in previous figures

The earliest capital of the Pyu, according to the Za-bu-kon-cha (page 29), Halin was first explored by archaeologists in 1905. Taw Sein Ko, director of archaeology, excavated ten sites, but was disappointed because the excavations did not yield the museum pieces he was seeking. His sites 1- 10 on the map (Figure 99), shown in black circles, are identified in the text as TSK to avoid confusion with the later excavated or explored sites which were numbered again from 1 in the 1960s by the Archaeology Department. The initial excavations were based largely on information from local people about discoveries of treasure, real or imagined. In one case, a site was excavated because someone had dreamed there was treasure buried there. Taw Sein Ko mapped the city walls and noted that the salt industry had denuded the area of fuel. Local people provided several silver coins and gold ornaments, and told the investigator that many bronze figures, coins or ornaments had been sold or melted down for the metal. These included figures of elephants, horses, bulls and serpents which had been dug up in a dry stream, TSK 7 (Figure 99). The now-vanished figures were described by the locals as having been filled with “medicinal or alchemical ashes”, although this might simply have been burnt clay cores from the lost-wax process. One useful find, at TSK 6, was a Pyu stone inscription which was attributed paleographically to the 4th century AD or earlier (AWB 1905: 7-10; ASB 1915: 21-23). This appears to be a funerary record, referring to the bones of Lord Ruba, son of Lord Davi-ni-mli and grandson of N-ga Kno. While not bearing a specific date, it provides three names of people who were most likely residents of the city, and of sufficient importance to merit commemoration in stone. Other Pyu inscriptions found at Halin (location of the finds is shown on the plan) refer by name to (King) Sri Trivigrama (Trivikrama) and Queen Candradevi (Luce 1985: 149, Vol 1). “Trivikrama” is the name of an incarnation of the Hindu god Vishnu, who can set foot on several worlds at the same time and conquer them (Nai Pan Hla 1972b). Aung-Thwin agrees that Sri Trivikrama appears to be a general royal title, and points out that Luce’s Queen Candradevi can also be read as Sri Jatradevi. Another stone mentions Mahadevi Sri Jatra (Aung-Thwin 2004 Ch 7). The vikrama suffix is shared with a dynasty at Sriksetra (see page 138). The South Indian script in the Sri Trivikrama inscription has been proposed as 8th-9th century AD (Aung Thaw 1972: 13).

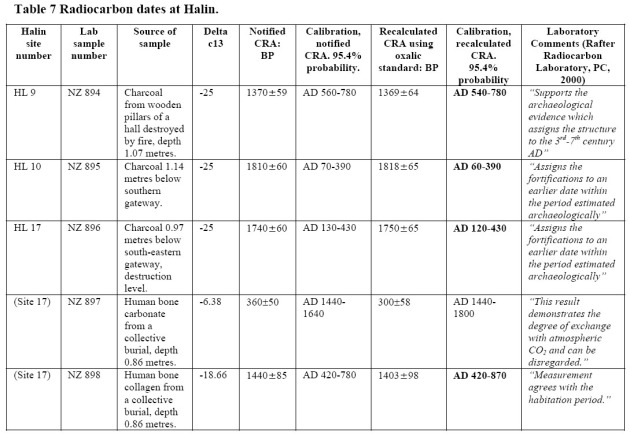

In 1930, Charles Duroiselle collected coins with a rising sun on one face and a srivatsa with swastika, sun, moon and dots ands lines on the other, which are now considered characteristic of the site (Mahlo’s Group 1), though they also appear at Maingmaw and Beikthano (Figure 85). He noted the discovery on the platform of a local pagoda of a Burmese stone inscription dated AD 1082-83 which mentioned a King “Sithu”, something of a generic name for kings of Bagan, as part of a dedication of land to pagodas and monasteries by the local governor. This date is earlier than any known inscriptions at Bagan. Duroiselle suggested that it points to Sawlu, the son of Anawratha (ASI 1929-30: 151-155). Inscriptions from Halin existing as copies, and dated AD 1081, 1082, 1086 and 1285, published in A List of Inscriptions in Burma, indicate activity from the 11th and 13th centuries (Duroiselle 1921: 5, 6, 62). A 12th century stone inscription in Burmese that had reportedly been found at TSK 5 (AWB 1905: 10) does not appear to be included in Duroiselle’s 1921 volume, even though the book drew on earlier lists compiled by Taw Sein Ko. Duroiselle recorded the presence of an inscribed sculpture featuring the lower part of a figure, possibly a bodhisattva, with rows of devotees below (ASI 1929-30: 154) that had been found beyond the north wall. In 2001, this was still on display at Halin in a specially built shed. Halin was systematically excavated by Myint Aung from 1962 to 1967, sites 1-19 on the map (Myint Aung 1970, 1975, 1979, 2003). Myint Aung returned in 1996 with a group of his students from Yangon University and excavated site 20 (Hla Tun Phyru 1996). The Mandalay Archaeology Department excavated sites 21-24 in 1998 (Pauk Pauk 1999b, 2001b). Further data came from field surveys in 2000-2001 by the author, Nyein Lwin and Win Maung. The four gateways so far excavated, sites 10, 11, 17 and 21, turn inward to the citadel, like the gates at Beikthano. A mound extending into the city at a right angle to the centre of the northern wall (E 95.81224° N 22.48867°) was surveyed in 2002 by the author and Nyein Lwin, and on size and orientation may be another gate. Sites 5, 8, 12, 13 and 15 appear to be ritual structures. Site 8, outside the wall, contained charred bones, burial pottery and gold ornaments. Earthenware funerary urns were found buried both within and outside the exposed structures, which were square or rectangular buildings with a quadrangular projection on one side in some instances. There are both skeletal and cremation burials within the walls of Halin. Site 17, which was radiocarbon dated (Table 7 & Figure 94), contained around 50 skeletons and disarticulated bones buried next to the brick wall and “below” Halin cultural material. The date suggests that the cultural material may have been redeposition from the burial. Site 20 contained up to 5 skeletons. Site 22 was a brick building with a group of unornamented megaliths, 1.5 metres high and 45 centimetres wide, arranged in front of it in a 5:4:1 pattern. Stucco heads and torsos were also found here (Myint Aung 1970). At another unspecified location, numerous skeletons were discovered together with funerary urns. Architecturally, the square or rectangular ritual structures, with no round stupas, seemed comparable with those at Beikthano (Aung Thaw 1972: 12, 15).

The general funerary picture is of a combination of cremation and inhumation burial. The excavation of disarticulated bones at HL 17 also points to a tradition of secondary burial. It may be worth considering that the notion that all pot burials at this site, and in early Myanmar generally, were “cremation” burials may be an interpretation based on investigator awareness of Buddhist and contemporary European cremations, and should be reconsidered. It may be that the presence of bones in a pot, rather than the presence of ash or carbonised bone, has been the archaeologists’ criteria for defining a cremation burial. From the archaeological reports of the early 20th century, at least, archaeologists showed a far greater enthusiasm for the pots than for their contents, though to be fair, they were working in an era when bioarchaeological methods for studying the contents had not yet been developed.

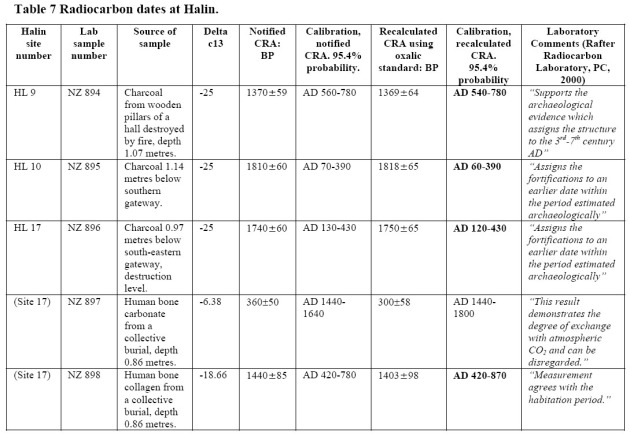

The radiocarbon dates from charcoal samples at Halin have been recalculated by the testing lab (personal communication, Dawn Chambers, Rafter Radiocarbon Laboratory, New Zealand, in an e-mail to Professor Mike Barbetti, Jan 27, 2000) since they were published by Myint Aung (Myint Aung 1970: 62). though only with minor variations from the original results. The lab has also produced dates from the same sample for human bone collagen and bone carbonate from site 17, which were not included in Myint Aung’s paper, but supplied to him later. The dates indicate activity at Halin between outside limits of AD 60 and 870. While cautioning that these are the outer ranges of the dates, it can be suggested that according to the available radiocarbon evidence, there may have been parallel activity with Beikthano, with its carbon samples showing an outer range from 180 BC to AD 540, over a period of 480 years (Figure 94). But there is a qualification, beyond the obvious need to caution that this is really a very small group of samples. The Halin samples include the only dates available specifically for first millennium fortifications in Burma, gates 10 (AD 60-390) and 17 (AD 120-430). The radiocarbon dates refer to the age range of the portion of the tree that provided the sample, and a gatepost may have required timber of substantial size. There is therefore an “old wood” problem, a dating issue that arises when there is no indication as to whether the sample was from sapwood or heartwood (Bowman 1990: 51). A sample from the outer trunk of a 200 year old tree, such as may have provided pillars or gateposts at Halin, will give a result 200 years later than a sample from the core of the trunk. Therefore it is reasonable to extend the possible range forward, and to consider that the construction phase of the gates and therefore the wall should be after AD 120, as the earliest possible date for the construction of both gates, if the sample from HL 17 came from the outside of the tree trunk, and possibly as late as AD 600 or so if both samples were from the core of 200 year old trees. It is not necessary, by this reasoning, to “assign the fortifications to an earlier date within the period estimated archaeologically” as per the lab comments (Table 7), but to consider that there may be a greater and possibly later range of dates for the construction of the fortifications than the two radiocarbon dates suggest.

The most reliable of the ANU thermoluminescence dates, for a potsherd at Gate 11, is AD 1050 (page 281), consistent with the epigraphic evidence of occupation during the Bagan period. Taking the same conservative view of the dates for Halin as for Beikthano, it can be suggested that the burial at site 17 may have been as early as AD 420 or as late as AD 870. Beyond the scarcity of absolute dates, there remains the problem of identifying sequences in a site where stratigraphy is difficult, not the least because, as shown by the regular appearance of stone axes in fields after rain or ploughing, there is considerable vertical movement on what appears to be a generally shallow archaeological horizon. Pyu Halin, like Beikthano, needs to be removed from the chronological restrictions imposed by the past interpretation of dating evidence, and its periodisation left more open until further evidence accumulates. The presence of the valuable salt resources at the site would be a motive for continuous occupation, and the gap between the last outer radiocarbon date of AD 870 and the thermoluminescence and epigraphic dates from AD 1050 to the 1080s is not necessarily evidence of a gap in the occupation of the site.

The “Gold Teeth” at Halin.

A heavy rainy season at Halin in 2001 followed by another uncharacteristically wet monsoon in 2002 uncovered artifacts which provide new evidence for continuity of occupation of the site since well before the period indicated by the radiocarbon dates (Nyo Win 2001b; Pauk Pauk 2001b). Most of this material has been reviewed in Chapters 3 and 4, but the find by farmers of an upper jawbone containing gold inlaid teeth just to the west of the Halin village cluster (Figure 99) is an example of the difficulty of data collection, periodisation and interpretation at Halin. The farmers were in the process of removing the gold from at least two skulls to sell when Win Maung was able to acquire one jawbone from them intact. The maxilla contains eight teeth that have been deliberately drilled on the front with holes, then the holes filled with gold foil (Figure 100). Each layer of foil would have contact-welded to the one below it. The intact coating of gold on the front incisors suggests that this was the sought-after effect for all the teeth. The pain of drilling must have been considerable. Earthenware containers thought to have been used for distilling alcohol (see page 85) have been found at Halin, so there may have been a crude form of anaesthetic available (Hudson 2003a).

The farmers who discovered the teeth had dug up a site which was marked by a group of large stone slabs. According to the author’s field notes from a visit with the landowners to the burial site later in 2001, after the finds had been removed, but with one of the stone slabs in question, 1.5 metres long by 40 cm wide, still to be seen in a ditch nearby, two skeletons had been found, heads pointed east, associated with iron hoes and knives as well as pottery. One skeleton wore gold and silver rings. A nearby burial (Figure 99) had skeletons whose heads pointed north, with associated painted pottery. These latter skeletons wore stone rings, and bronze rings and bracelets made of what appear to be coiled strips of beaten bronze. The grave goods and the orientation of the bodies would suggest a different and earlier burial practice.

Gold work in dentistry has been recorded in Italy as early as 700-600 BC, where a gold band riveted to a reused tooth was used to return the tooth to the jawbone by binding it to its two neighbours (Teschlor-Nicola, Kneissel, Braundstatter et al. 1998). Other Etruscan examples of the same period have been recorded, and in the 5th and 4th centuries BC Phoenicians repaired teeth with gold wire (Clawson 1934). An early use of gold foil as a dental therapeutic agent is mentioned in Artzney Buchlein, published anonymously by a German physician/dentist in 1530, in which the operation is quoted from Mesue (AD 857), physician to the caliph Haroun al-Raschid. The dental use of gold foil was known in Britain from the 16th century, and became widespread in 19th-century Europe and the USA (Travers 1994; Cox, Chandler, Boyle et al. 2000). The teeth from Halin appear to have been modified for cultural rather than therapeutic reasons. The pre-Columban Maya, Aztec and Inca were known to inlay teeth with jade or iron pyrite, a practice dated to AD 500-900 (Alt & Pichler 1998). Modified teeth bearing small gold discs fixed into the teeth with gold pegs have been found at Bolinao in the northern Philippines, and dated to the 14th-15th centuries AD. Another of the Bolinao finds consisted of a moulded gold plate wired to six upper teeth (Legaspi 1974). The National Museum of the Philippines has a collection of teeth with gold pegged lozenge and floral shaped decorations as well as discs. These are broadly attributed to the period after AD 1200 (Winters 1977: 451-452).

A similar collection including gold discs and plates, excavated in the 1920s at 3 separate sites in the southern Philippines, was held by the Museum of Anthropology at the University of Michigan. Some of these finds had been associated with Chinese trade ceramics of the Sung Dynasty (AD 960-1279). The habit was recorded historically in the Philippines in the 16th and 17th centuries, and described ethnographically in the Philippines, Sumatra and Borneo. The inlaying seems always to have involved gold, or at times brass, wire and pegs rather than foil (Guthe 1935). This kind of tooth decoration in the Philippines has been viewed as a mark of rank and high social status in the highly competitive post-European contact period, the early to mid-second millennium AD (Junker 1999: 124, 177-178, 348, 365) There are references to this form of body decoration relevant to Myanmar in the Chinese historical record. From the Tang Dynasty (AD 618-936) onwards, the Wa and other tribes living between the Mekong and the Salween were known to the Chinese as the Chin-ch’ih, or Gold Teeth. The Man Shu, or Book of the Southern Barbarians, published in AD 860-873, lists the Gold Teeth along with other groups including the Silver Teeth, the Tattooed Legs and the Black Teeth. The Chinese chronicler reported that the Black Teeth lacquered their teeth, although he may have been describing people who chewed arecea (“betel”) nut, whose teeth can look quite black. The Man Shu also says the Gold Teeth “use gold carved plates to cover their front teeth” and remove them to eat (Luce 1961). The Chinese chronicler may in this case be describing an entirely different phenomenon to the Halin teeth, such as the Bolinao gold plate in the Philippines, or he may be repeating a confabulated description. Chinese reports of the Gold Teeth people appear over a period of at least 500 years. The Gold Teeth were among the tribes who submitted when the Mongols captured Kaungsin, 250 kilometres north of Halin on the upper Ayeyarwady, in 1283 (Luce 1969: 37). The P’iao (Pyu) are mentioned as one of the tribes of the “Gold Teeth Comfortership” in the Yuan Shi, or History of the Yuan Dynasty, which was completed in AD 1370 (Luce 1985: 66; Sun Laichen 1997: 20). On the basis of the Chinese references, then, the Halin gold teeth might date from the 7th century AD or later. However the burial context was individual, with megaliths and grave goods suggesting that it was not related to the communal system of urn or inhumation burials that is associated with Pyu brick platforms. The jawbone must, at least, post-date the availability of gold foil. The grave was originally found because the stone slabs covering it were close enough to the surface for the plough to hit them. These issues point to the need for further absolute dating and bioarchaeological analysis.

Hanlin Archaeological Map

Hanlin Local Region And Satellites

The Halin hinterland.

The hinterland of Halin (Figure 96) contains walled sites that sit at a consistent distance away,and it is worth considering whether they may form some kind of defensive or administrative circle. During World War II, British and Japanese soldiers in Burma had a daily combat marching range of 30 to 40 kilometres (Allen 2000: 79, 123). This supports Hansen’s general figure of a 30 kilometre administrative/defensive “day’s march” radius for a self-contained city-state (Hansen 2000: 16-19). There are at least nine walled sites within this range of Halin. An apparent burial urn (Figure 97) that is difficult to place in the existing Pyu urn typology (Hla Tun Phyru 2003) and a bowl with what may be Pyu writing (Figure 98) have been found at Shagwe. Coins bearing auspicious symbols were found at Minkyi. Sitha is said locally to be a Bagan period fort (Ernelle Berliet, personal communication 2003). Hladwe has a 13th century inscription. Siboktra shares a distinctive cup shape, an oval with a flat end, with several well-attested Bagan period sites of the Panlaung/Kyaukse district (Win Maung 2000b). Further investigation of these sites should provide a better indication of whether they were related to Pyu Halin, or whether they were outposts of Halin in the Bagan period, demonstrating its importance as an administrative and resource centre.

Radiocarbon Dates at Hanlin

REF : The Origins of Bagan. The archaeological landscape of Upper Burma to AD 1300.

By Bob Hudson. University of Sydney. 2004

သိပ္ေကာင္းတဲ့ Myanmar Archaeologists site ပါ။

ေကာင္းတယ္ဗ်ာ…ေသခ်ာလုပ္ထားတဲ့အတြက္ အဆင္ေျပတယ္… အဆင္ေျပတဲ့အတြက္ ေက်းဇူး….

အရမ္းေကာင္းတယ္။ ဒီ Seite ကိုၾကည့္ခြင့္ရလို ့ေက်းဇူးတင္ပါတယ္။

ေလးစားပါတယ္၊

Nice idea! keep up the good work. Beatles

သိပ္ေကာင္းပါတယ္။ ေရွးေဟာင္းသုေတသနပညာ ကို ေလ့လာခ်င္တဲ့သူေတြအတြက္ အသုံး၀င္တဲ့ Website တစ္ခုပါ။ ဒီထက္ပိုၿပီး ျပည့္စုံေအာင္လုပ္ေပးပါဦး။

I find a very interesant site – you must look: radia samochodowe|urzadzenia wielofunkcyjne

I would like to suggest you to change black background to white background. It is an academic site and black background attack readers eyes and lose concentration.

best

Moethee zun